How Did Bumpy Johnson Die

- Born: December 24, 1897, probably on French Guadeloupe Died: December 1969, Central Islip, New York Nicknames: Queenie, Madam Queen, Madam St. Clair, Queen of the Policy Rackets Associations: Bumpy Johnson, Dutch Schultz, Lucky Luciano. Clair carved out a piece of the New York rackets during the early years of the 20th century, battling mobsters such as Dutch.

- Godfather of Harlem is an American crime drama television series which premiered on September 29, 2019, on Epix. The series is written by Chris Brancato and Paul Eckstein, and stars Forest Whitaker as 1960s New York City gangster Bumpy Johnson.Whitaker is also executive producer alongside Nina Yang Bongiovi, James Acheson, John Ridley and Markuann Smith. Chris Brancato acts as showrunn.

Born: December 24, 1897, probably on French Guadeloupe

Died: December 1969, Central Islip, New York

Nicknames: Queenie, Madam Queen, Madam St. Clair, Queen of the Policy Rackets

Associations: Bumpy Johnson, Dutch Schultz, Lucky Luciano

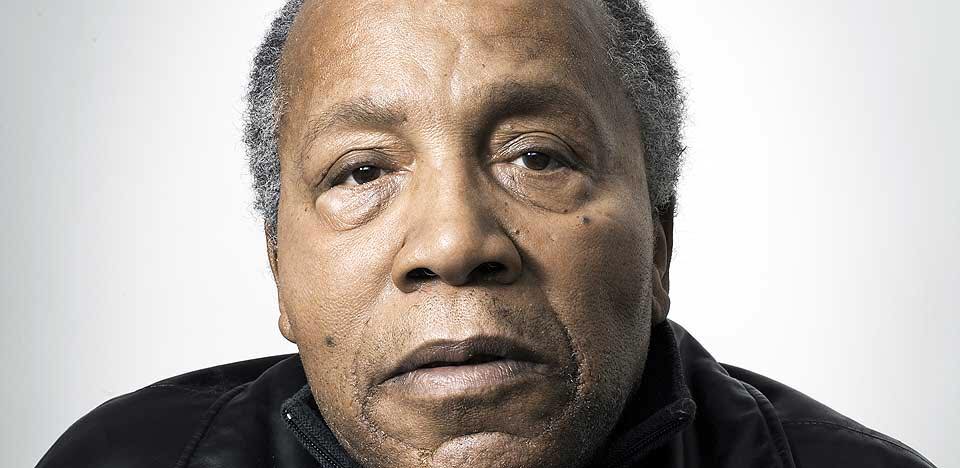

The American Gangster true story reveals that Ellsworth 'Bumpy' Johnson died in 1968 while eating at Wells Restaurant on Lenox Avenue in New York City (Philadelphia Daily News). The movie's location of an appliance store was used to represent Bumpy's disgust with. Ellsworth Raymond 'Bumpy' Johnson died of a heart attack in 1968. Despite the claim made by his driver, Frank Lucas, Bumpy Johnson's widow claims that Lucas was not present with Bumpy Johnson when Johnson had that fatal heart attack. Frank Lucas made much of his claim, and asserted his right to claim Bumpy Johnson's position atop the Harlem.

Stephanie St. Clair carved out a piece of the New York rackets during the early years of the 20th century, battling mobsters such as Dutch Schultz and Lucky Luciano, as well as corrupt and honest police, for control of gambling in Harlem.

According to biographer Shirley Stewart, who wrote the definitive history of St. Clair, she was born in the French east Caribbean island of Guadeloupe in 1897 and traveled to the United States on a steamer in 1911 when she was 13 years old. Other biographies echo the manifest of the S.S. Guiana, aboard which St. Clair traveled, and they peg her age at “about” 23 when she arrived in New York, with an 1887 birthday – a full decade earlier. St. Clair was an educated woman by the standards of the French Caribbean and certainly would have known her age, so it’s not clear why there would be uncertainty about this – unless she wanted that uncertainty.

There are other obvious discrepancies between St. Clair’s commonly repeated biography, a product of the yellow press of the period, and Stewart’s well-researched effort. Among them: Some sources say St. Clair lived for a time in Marseilles, France. Stewart disputes that. Stewart also says St. Clair, after arriving in New York in 1911, initially passed through and worked as a domestic servant for a family in Canada before returning to the New York five years later. In any case, after returning to the United States, St. Clair’s background in the French Caribbean gave her an education that allowed her to read and write in both French and English, a significant professional advantage at the time.

One thing biographers agree on: St. Clair settled into the growing African-American community of Harlem on the northeast side of Manhattan. St. Clair probably repeated many of the myths that ultimately formed her “official” biography. Certainly, as a resident of Guadeloupe, she would have spoken French and could have passed for many people as a former resident of France.

She arrived just a few years ahead of the Great Migration, which saw millions of African-American men and women leave the harsh repression of the Jim Crow South for relatively free Northern cities such as New York. Early on she became a leader of a local gang, the 40 Thieves, that ran extortion and theft rackets. St. Clair also invested $10,000 to develop a numbers racket – in the vernacular, she became a “policy banker.”

The numbers racket was a lottery similar to those in Hispanic and Italian communities called “Bolitos” but specifically designed for the African-American community. It made her wealthy, but it also made her a target, especially when the repeal of Prohibition loomed and mobsters such as Dutch Schultz were looking for new rackets to replace their alcohol profits.

She was described by contemporaries as arrogant, sophisticated and educated. St. Clair also was capable of scathing profanity and she was well-known for her fierce temper, which was often directed at rivals, including police and white-owned businesses that intruded on her Harlem turf.

For years, St. Clair developed and banked the lucrative numbers rackets in Harlem, in partnership with her lieutenant, another well-known African-American mobster, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson. About 1930, other mobsters started moving in on the numbers rackets. Schultz, born Arthur Flegenheimer, a Mob boss of legendary temper and violence, was her chief rival. While the nation was looking at the bloody toll of the Chicago Beer Wars that included the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, the corpses were piling up in Harlem as well: At least 40 people were killed in gang violence that centered on control of the numbers.

Despite their efforts to hold on, which included alerting municipal authorities to Schultz’s deprivations, St. Clair and Johnson saw their control of the numbers rackets slipping. St. Clair simply did not have the contacts with the police to protect her turf, although her testimony to a police investigatory commission led to the dismissal of some officers.

By the mid-1930s, St. Clair, who had lost the support (if not the affection) of Bumpy Johnson by this point, realized Schultz and the Mafia led by Charlie “Lucky” Luciano had too much power to resist and she turned over her organization to those rivals.

Schultz, however, had other problems on his doorstep. As the No. 1 mobster in New York City, he was targeted by crusading District Attorney Thomas Dewey. Schultz decided to assassinate Dewey, a decision that caused consternation in Luciano’s camp: Certainly such a move would only bring more unwanted legal scrutiny of the varied Mob rackets.

Luciano, who at this point was the self-titled “chairman of the board” of the Five Families of the New York syndicate, refused to authorize the hit on Dewey. When Schultz prepared to go ahead with the assassination, Luciano instead had Schultz killed. Assassins shot Schultz and killed three of his associates on October 25, 1935. Schultz, gut-shot and delirious, lived for almost a full day, long enough for St. Clair to send him a telegram that read, simply, “As ye sow, so shall ye reap,” a Bible verse from Galatians 6:7.

About a year later, St. Clair, still wealthy thanks to smart investments but no longer in command of her numbers empire, married the leader of an Islamic-Buddhist cult, and by some accounts something of a con man, named Sufi Abdul Hamid. Hamid claimed among other things to be a descendent of Egyptian pharaohs. According to chronicler Sumithra Naidoo, Hamid was known as an anti-Semite, the “black Hitler of Harlem,” and was convicted of stabbing a communist organizer in 1936.

Hamid’s flamboyant clothing and dramatic community presence may have matched St. Clair’s, who now was a self-styled civil rights advocate writing frequent letters to the editor in the black press, but their relationship was tempestuous from the start. In January 1938, Hamid was shot on his way to see a lawyer, and St. Clair was charged with the crime. She insisted that if she had wanted Hamid dead, he would be dead.

During the sensational trial that followed, St. Clair’s lawyer was able to get Hamid to admit that his name was really Eugene Brown, that he was from Philadelphia and that he had a mistress named, improbably, Madame Fu Fattam, who peddled mystical potions.

The all-white jury convicted St. Clair of assault and she was sentenced to 2 to 10 years in state prison.

When she left prison, she continued to work for civil and economic rights for African-Americans, but seemed to steer clear of criminal enterprises. Apparently, she had the “protection” of her colleague Bumpy Johnson until he died of a heart attack in 1968. St. Clair died 18 months later.

Born: January 20, 1883, Atlantic County, New Jersey

Died: December 9, 1968, Northfield, New Jersey

Nicknames: Nucky, Czar of the Ritz

Associations: Al Capone, Charlie “Lucky” Luciano, Meyer Lansky, the Commission

Enoch Lewis “Nucky” Johnson was the Prohibition Era kingpin of the Atlantic City political machine who personally and professionally benefited from Prohibition, which was essentially a dead-letter law in Atlantic City. A large man, over six feet tall, Johnson was famous for wearing a red carnation in the button hole of his impeccable suits.

Johnson, who inspired the Nucky Thompson character in the HBO television series Boardwalk Empire, was the son of the sheriff of Atlantic County, a powerful regional politician in his own right. Johnson followed in his father’s footsteps and was elected Atlantic County sheriff in 1908. A year later, Johnson was appointed executive secretary of the county’s Republican Party.

In 1911, New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson, a reformer who would go on to be president, led an effort to clean up corruption and rackets in Atlantic City, leading to indictments of more than 100, including Johnson and the then-boss, Louis “The Commodore” Kuehnle. While Kuehnle was convicted of election fraud, Johnson was not. Although he was forced to resign as county sheriff, he assumed near-total control of the Republican Party machinery for Atlantic City and Atlantic County. Johnson, who reportedly got a percentage of profits from all gambling and prostitution in Atlantic City, soon extended his political influence into state politics and was instrumental in the election of a sympathetic New Jersey governor in 1916.

With the enactment of Prohibition in 1920, Johnson’s profits and political influence continued to grow. Prohibition was essentially ignored in the coastal holiday community. In 1929, Johnson hosted a meeting of prominent Mob figures, including Charlie “Lucky” Luciano, Meyer Lansky and the participants in Chicago’s beer wars, Al Capone and Bugs Moran.

By the 1930s, newspapers and law-and-order reformers started paying close attention to Atlantic City and to Johnson. Johnson, famously, did not apologize for delivering illegal products to paying customers. “We have whisky, wine, women, song and slot machines,” he said. “I won’t deny it and I won’t apologize for it. If the majority of the people didn’t want them, they wouldn’t be profitable and they would not exist.”

Johnson’s public persona attracted the wrong kind of federal attention. He was indicted and tried for tax evasion. In one investigation cited by Thomas Reppetto in American Mafia: A History of Its Rise to Power (2004), Treasury agents counted the number of towels in local brothels to estimate the number of customers and thus the amount of income that went to Johnson.

After three trials, federal prosecutors finally won a conviction and in 1941 Johnson began serving a ten-year sentence. He was paroled in 1945, and lived more modestly and quietly in Atlantic City while he worked as a salesman for an oil company. But he continued to be influential in local and state politics.

How Did Bumpy Johnson Die In Witness Protection System Images

Unlike his fictional Boardwalk Empire counterpart, who was shot and killed, Johnson lived into old age. He died at age eighty-five in a convalescent home in New Jersey. That wasn’t the only difference from his fictional alter ego, Nucky Thompson. Johnson was never alleged to have personally killed anyone, nor was he accused of ordering someone else’s murder. His approach was to rule with money and influence, rather than violence: “Johnson ruled with a velvet hammer. His power was such that he never needed violence to get his way,” the New York Times wrote in 2014.